NOAA wind forecasts result in $150 million in energy savings every year

While wind is abundant, it is also intermittent. Utilities need accurate wind forecasts in order to gauge electricity production - and to determine when they need to generate or purchase energy from other sources when winds abate. Poor forecasts can cost a utility a lot of money, and those costs are then passed on to consumers. Accurate forecasts, however, can result in more efficient generation management and substantial savings. But it's not always clear what those savings are.

A study published by the Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, economists and scientists from Colorado State University and NOAA’s Global Systems Laboratory puts a number on just how impactful NOAA’s HRRR model has been. The research team calculated that increasingly accurate weather forecasts over the last decade have netted consumers over $150 million per year in energy savings.

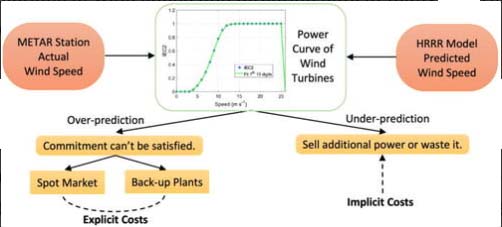

“This study investigated the cost to the utilities of both ‘overprediction’ - when the weather forecast predicted too much wind - and ‘underprediction’,” said Dave Turner, manager of the Global Systems Laboratory’s Atmospheric Science for Renewable Energy program. “Overprediction required the utilities to purchase energy off the spot market, while underprediction resulted in costs associated with the unneeded burning of fossil fuels.”

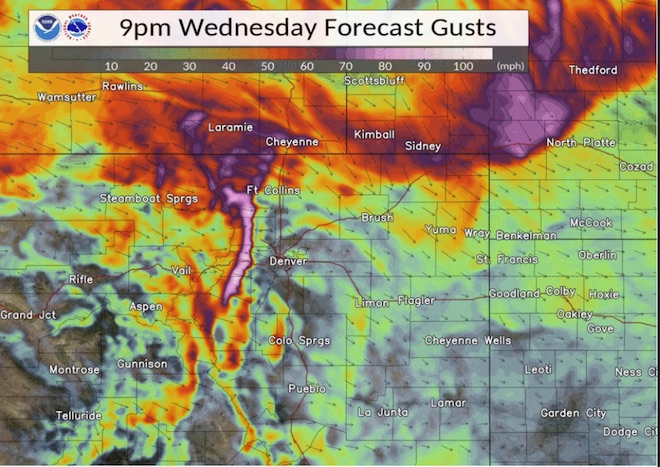

To quantify the economic benefit of more accurate wind forecasts, scientists compared the outputs generated by older and newer versions of NOAA’s High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) weather model, which provides hourly updated forecasts for every part of the United States out to 48 hours. The model generates predictions of wind speed and direction data at many different levels of the atmosphere, which utilities can employ to gauge how much energy their turbines will produce.

“We were able to compare these models side by side and see when one model makes a better prediction than the other,” said study co-author Martin Shields, an economics professor at Colorado State University. “And what we see over time is that the models get better at predicting wind and that generates additional savings for utility consumers.”

Every few years, NOAA researchers transition an updated version of the HRRR to National Weather Service operations. At the same time, researchers are already working on the next update in line, running it in real time with current weather observations on the Jet supercomputer at their Boulder, Colorado lab. This allows researchers to compare each model’s forecasts to actual conditions during those overlapping years to measure just how much each model improved over its predecessor.

Advances in wind forecasting were aided by the results of two research projects supported by the Department of Energy, including a 2015-2019 study focused on improving the physical understanding of atmospheric processes that directly affect wind energy forecasts in the complex terrain of the Columbia River Gorge, where several hundred wind turbines are powered by winds coming off the Pacific Ocean.

Economists at CSU can assign a cost to every deviation between a predicted wind speed and a measured wind speed, from either needless operational expenses, or the price of extra electricity purchased from the wholesale market to backfill over-predicted winds. By looking at the difference in errors from each model the researchers were able to put a dollar sign on each upgraded model.

During the overlap period from HRRR 1 to HRRR 2 in 2015, and from HRRR 2 to HRRR 3 in 2017, the team calculated that if utilities had been using the newer model instead of the older one, they would have saved approximately $384 million per year, most of which would have been passed on to consumers.

“The researchers at NOAA have been struggling for a long time to put a value on their forecast,” said Shields. “They know their models are getting better, they know that people use those in important economic decisions, but they have a hard time quantifying exactly what the value of that is.”

Researchers are now planning to evaluate another benefit the HRRR offers to the renewable energy industry, namely improved cloud cover forecasts for solar power providers.

* Adapted from an American Institute of Physics press release.